2043 Views

The Middle Corridor Mirage: Why Central Asia Risks Serving Europe and Turkey, Not Itself

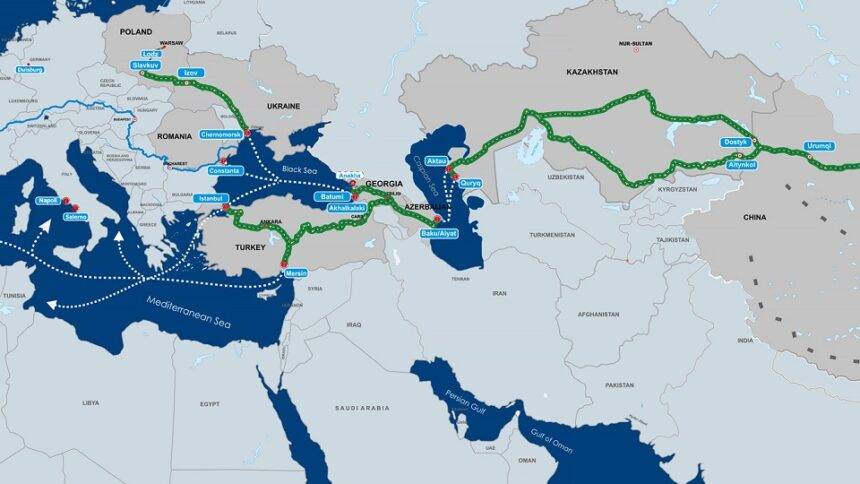

The Middle Corridor, also known as the Trans-Caspian Corridor, was initially introduced as an alternative route linking China and Central Asia to Europe via the Caspian Sea, the Caucasus, and Turkey. At first glance, it appeared to be a practical and attractive plan that could safeguard the interests of Central Asian states. However, over time and with a deeper look into the geopolitical, political, and economic realities of the region, it becomes evident that this route has primarily been designed to serve the interests of Turkey, Europe, and extra-regional powers rather than to genuinely benefit or protect the interests of Central Asia.

Now, with the implementation of the project becoming more serious, the high logistical costs (rail-sea-road) and the weakness of port infrastructures along the western Caspian have practically undermined the corridor’s efficiency.

On the map, this route may appear to provide a suitable pathway for Europe and potentially reduce its dependency on Russia. But experts argue that the corridor not only faces serious infrastructural constraints but also entails higher costs and nearly twice the transit time compared to the traditional Russian route. In practice, the cost of transporting a 40-foot container via the Middle Corridor is estimated at $3,500– $4,500, while the same shipment through Russia costs approximately $2,500– $3,200. Moreover, the corridor currently handles only about 5% of the region’s freight volume, and in some cases, delivery may take up to 40 days. Thus, it seems the corridor is more symbolic and political than functional or economically viable for regional states.

Although it outwardly appears to be a direct connection between China, Central Asia, and Europe, the corridor’s numerous transit stages, logistical complexities, and multi-layered coordination requirements turn it into an expensive and time-consuming puzzle. Cargo must first be transported from Kazakhstan to Caspian ports, shipped across the sea to Azerbaijan, and then carried by rail and road through Georgia before finally reaching Turkey and Europe. Each stage requires separate management, customs coordination, and modal shifts, which increases risks and leaves the corridor at a competitive disadvantage compared to alternatives—particularly the Iranian route. Ultimately, this creates challenges for Europe rather than solving them.

The Middle Corridor is also exposed to geopolitical vulnerabilities and political risks. Security instability in the South Caucasus, and the possibility of renewed conflict after the Second Karabakh War, make the corridor fragile. Moreover, international sanctions, shifts in foreign policy, the influence of external actors, and Turkey’s ambitions for greater regional penetration cast further uncertainty over its future.

Contrary to Western expectations, Central Asian states continue to benefit from trade via Russia. Officials in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan have demonstrated that, despite Europe’s emphasis on the Middle Corridor, they still prefer to move goods through Russia, as this is more logistically and economically viable—even though it exposes them to secondary sanctions. These sanctions, targeting not only Russia but also any country trading with it, increase costs. Yet, before the Ukraine conflict, the Russian route carried over 90% of rail traffic between Europe and the Far East. Western sanctions have not only restricted traditional routes to Europe but also accelerated Eurasian integration.

Today, Russia needs Central Asian states more than ever to sustain its trade and energy flows, giving these countries a unique opportunity to elevate their geoeconomic role. Over recent decades, Central Asia’s role has evolved from being merely a buffer zone between Russia and China—or between East and West—to becoming a vital bridge linking East–West and North–South. This has been fueled by its strategic geography, expanding rail and road networks, and growing foreign investment in transit infrastructure.

Indeed, after this geoeconomic transformation, no Eurasian trade route can remain sustainable without the full participation of Central Asian states. New initiatives such as the Middle Corridor will remain ineffective without their consent and involvement.

In conclusion, while the Trans-Caspian Corridor may appear to offer an alternative to bypass Russia, in practice it has proven inefficient due to high costs, delays, logistical uncertainties, and political risks. Geopolitical instability in Central Asia and the South Caucasus, Turkey’s ambitions, Western neo-colonial tendencies, and the lack of alignment among regional stakeholders make its future fragile and uncertain. At the same time, despite secondary sanctions and Western pressure, Central Asia remains dependent on Russia and its transport routes. Yet this same pressure is reducing Russia’s reliance on Europe and pushing it toward greater Eurasian integration.

All of this ultimately creates a paradox built upon one central question: Will the Middle Corridor truly secure the interests of Central Asian states—or those of extra-regional powers? A question whose answer may only be revealed with time.

Translated by Ashraf Hemmati from the original Persian article written by Navid Daneshvar

Comment

Post a comment for this article