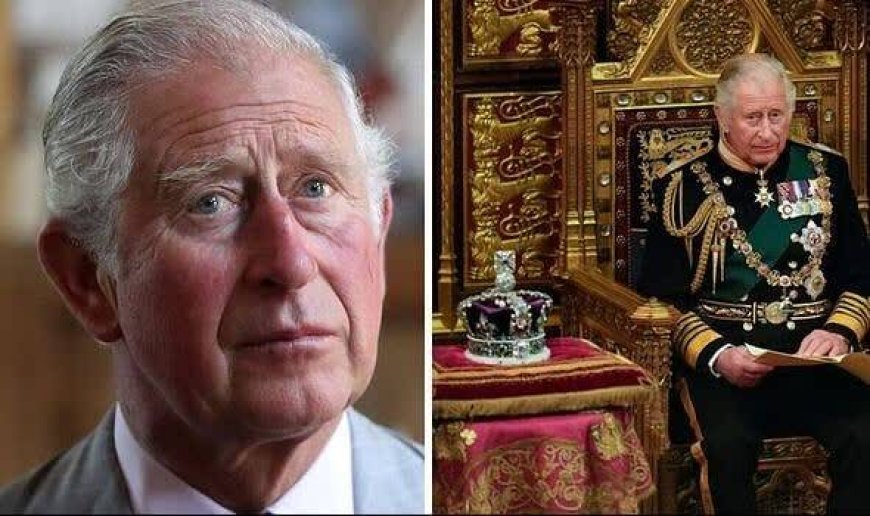

How the British royal family hides its wealth from public scrutiny

Ahead of the coronation of King Charles III, the Guardian’s Cost of the crown series exposes the entrenched secrecy around the royal family’s money and wealth by David Pegg and Paul Lewis

ow much money will the coronation of King Charles III cost the British public? What tax rate will our new king pay on his private income? How many engagements did “working royals” such as the Dukes of Gloucester and Kent attend over the last five years? How much were they paid? How much rent do Princesses Beatrice and Eugenie, who are not working royals, pay for residences in royal palaces?In recent weeks, the Guardian has posed all of these questions to Buckingham Palace. The responses boil down to “ask someone else”, “work it out for yourself”, or simply “you have no right to know”. We beg to differ.

Obituaries of Queen Elizabeth II uniformly applauded her calm stewardship of the realm, or her supposed non-interference in British politics. None mentioned another hallmark of her reign: entrenched secrecy, which has given rise to a culture in which the British people are deprived of the most basic information about the monarchy.

Correspondence with the monarch or the heir, whether seismic or harmless, is banned from disclosure. Parliamentary criticism of conduct of royal family members, no matter how disgraced, is prohibited. The palace says the royal archives – the repository of our constitutional monarchy’s history – are open to “any serious researcher”. However they are the private property of the Windsors, who grant their permission before researchers can examine them.Nowhere is the refusal to let the light in more fiercely enforced by the royals than over financial matters. The wills of even obscure members of the family are censored by judicial decree. The royals closely guard the secrets of their financial wealth, insisting it is “private” even when it is clearly born of their public roles.

It should not detract from Elizabeth II’s achievements to observe how this addiction to secrecy allowed the most unacceptable and corrosive practices to take root. In the past three years, official papers uncovered by the Guardian have revealed how the Queen and her advisers repeatedly abused the procedure of crown consent to secretly alter British laws, including, in 1973, as part of a successful bid to conceal her “embarrassing” private wealth from the public. Until at least 1968, and very probably after, Elizabeth II’s household did not appoint “coloured immigrants or foreigners” to clerical roles, although they were permitted to work as domestic servants. Even today, Buckingham Palace insists it only complies with non-discrimination law voluntarily. Does the king approve of this? What other abuses have yet to be revealed? And how are they going to come to light when the monarchy is exempt from the Freedom of Information Act (FoI)?

Today, the Guardian is launching Cost of the crown, an investigation into royal wealth and finances. In the coming days and weeks, our reporting will reveal information in the public interest about the fortunes that have been quietly amassed by the royals by dint of their public function. Our reporting will also demonstrate the vast challenge of obtaining answers to the most simple of questions.Take, for example, the question of how much public money is spent on security for the royal family. The government, so often the monarch’s ally over matters of secrecy, claims that to disclose even just a single totalised figure for the entire family, without any further details whatsoever, would constitute an unacceptable threat to their safety.

It refuses to explain this reasoning in any detail, or why heads of state in other developed countries, including French and US presidents, can publish details about the costs of their security. Instead, an FoI request to disclose the security costs of British royals was rejected, first by the Home Office and then, on appeal, by the Information Commissioner’s Office – forcing the Guardian to instruct lawyers last month to bring a further appeal at the information tribunal. To say it will take months to get an answer would be optimistic.

It took our colleague Rob Evans 10 years and a trip to the supreme court to secure the release under FoI of Prince Charles’s “black spider memos”, which showed how the heir to the throne lobbied senior government ministers on everything from badger culling to alternative herbal medicines. The government spent more than £400,000 on legal costs in an ultimately failed bid to keep the memos secret.