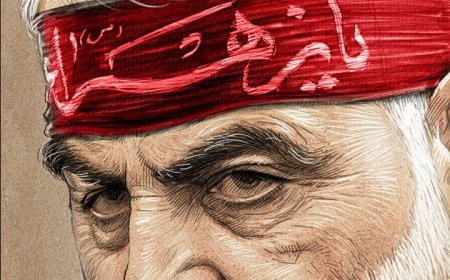

The Downfall: Will the arrest of Tunisia's Ghannouchi signal the doom of liberal Islamist parties?

The Downfall: Will the arrest of Tunisia's Ghannouchi signal the doom of liberal Islamist parties?

By: S. Gol-Anbari

Although repeatedly securing parliamentary majorities over the last decade, Ennahda has shown that its interpretation of Islam is the most progressive. For instance, in the debate over the new Tunisian constitution after the revolution of 2011, it was decided that Islam would not serve as the primary source of law. In 2012, the Ennahda-controlled Tunisian parliament passed a law allowing the sale and purchase of alcoholic beverages.

Several Islamist groups, most notably the Salafists, opposed the Ennahda-led governments and their more moderate policies. To be clear, Ennahda's policies in this respect weren't driven by a desire to disregard Islamic law but rather by the notion that involving the state in the enforcement of Islamic law would have the opposite effect. Back then, Ghannouchi shared the general view that community-based efforts and civil campaigns were the most effective way to reduce alcohol sales and use. The moderate branch of the Muslim Brotherhood has argued that Sharia, the Islamic law, should not be enforced by the state. Instead, they advocated for the realisation of higher religious ideals and fundamental values, such as justice, equality, and freedom.

However, the Arab armies and shadow governments quickly overthrew even these progressive Islamists in power, demonstrating that their presence in power was intolerable. As such, Mr. Ghannouchi’s arrest and the subsequent closure of Ennahda offices can be seen as not only the end of the "Arab Spring," but also the end of the Muslim Brotherhood's presence in power, which after 2011 emerged as the most organised party in the position of an alternative to the secular dictatorial systems, assuming power in several countries. Over time, the Ennahda movement was subjected to scrutiny, internal criticism, and a reevaluation of the nature and manner of its political activism. The arrest of Ghannouchi, experts say, would undoubtedly hasten this reassessment. Abdelilah Benkirane, Morocco’s Justice and Development Party Secretary-General, has argued that the Brotherhood's pursuit of power was their worst mistake.

The political upheavals since 2011 have dissuaded the Muslim Brotherhood from pursuing the bottom-up, incremental social reforms that once were central to their social doctrine decades ago, as, whether by accident or design, they attempted to gain political control from the top-down. The Muslim Brotherhood made another fatal error by failing to have a comprehensive plan in various aspects of governance, particularly economics. Following their ascension to power, they were confronted with an accumulation of socioeconomic crises resulting from decades of corrupt secular dictatorship; however, they had not yet concluded the nature of government and the relationship between religion and power.

Obviously, this does not imply that the rival secular parties had or have panaceas for their nations' maladies. In fact, the current financial predicaments in Egypt and Tunisia may be traced directly to the secular parties' poor administration, despotism, and failed governance. The Muslim Brotherhood's doom can also be attributed to their underestimating the nuanced nature of politics, regional and international dynamics, and the Zionist regime's constantly present role. Finally, the non-democratic secular rivals, who enjoyed the endorsement of the power centres, including the army, could wrest power again.

If Islamists and other democratic and leftist movements opposing Arab dictatorial systems fail to realise that political change cannot be accomplished merely through political engagement, the status quo will persist. The current bleak situation would be different if the Muslim Brotherhood's efforts to gain power were instead applied to political growth and civil initiatives.

In societies ruled by dictators for millennia, despotism penetrates people's subconscious to such an extent that it manifests itself in both Islamist and secular forms. Nothing will improve with top-down reforms until the pervasive tyrannical culture is eradicated.