The Boundaries of Madman Theory

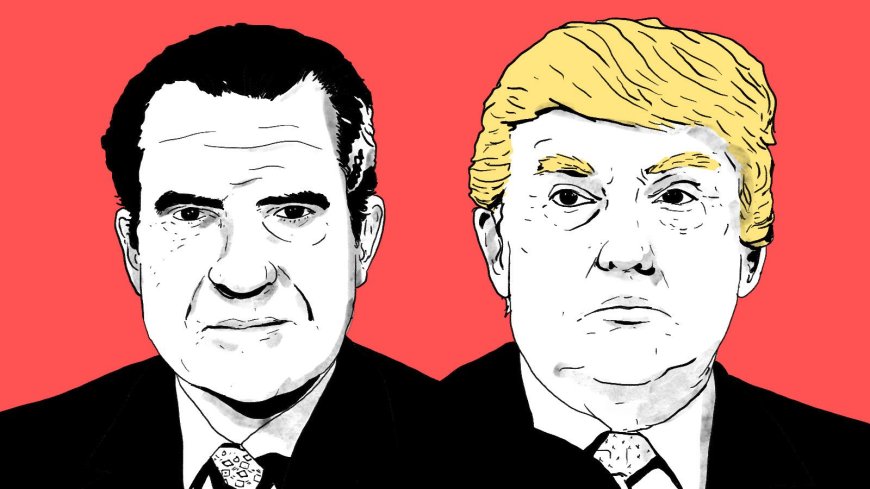

Donald Trump asserts that his reputation for unpredictability is an asset of U.S. foreign policy. Since his 2016 campaign, he has emphasized the importance of being "unpredictable," describing it as a strategy to maintain adversaries' attention.

Donald Trump asserts that his reputation for unpredictability is an asset of U.S. foreign policy. Since his 2016 campaign, he has emphasized the importance of being "unpredictable," describing it as a strategy to maintain adversaries' attention.

This philosophy was reflected in Trump's actions during his first term. He transitioned between diplomatic gestures and aggressive rhetoric, including menacing North Korea with "fire and fury" prior to his appointment as the first U.S. president to meet its leader.

Advocates, including Vice President JD Vance, have contended that this strategy has been advantageous to the United States, citing instances such as compelling Israel to negotiate a ceasefire or preventing Russia from invading Ukraine. However, the long-term efficacy of Trump's so-called "madman" strategy in international relations is called into question.

Madman theory is not a novel concept. As early as the 16th century, Niccolò Machiavelli promoted the use of simulated lunacy as a political strategy. During the Cold War, modern applications were developed by strategists such as Richard Nixon, who employed the concept to create an appearance of instability that would intimidate adversaries into submission. Nixon famously directed his advisors to persuade North Vietnam and the Soviet Union that he was capable of anything, including nuclear conflict.

Other leaders, such as Saddam Hussein, Khrushchev, and Qaddafi, also developed reputations for irrationality, although the outcomes were frequently inconsistent. Although the theory has the potential to increase the credibility of threats, it is rarely implemented effectively, as history has demonstrated that agreements can be undermined by being perceived as untrustworthy.

Madman theory has consistently failed to produce decisive results, despite its theoretical appeal. The ability to convert perceived unpredictability into strategic victories was a challenge for leaders such as Nixon, Khrushchev, and Saddam. Khrushchev, for example, issued dramatic threats during the Cuban Missile Crisis but ultimately relented, which diminished his credibility.

Likewise, Saddam's demise was precipitated by his aggressive stance, which convinced U.S. policymakers that he was uncontrollable due to his perceived insanity. The inherent paradox of madman theory is illustrated by these examples: it may compel opponents to take threats seriously, but it also raises doubts about whether agreements or concessions will result in stability, thereby making adversaries less inclined to cooperate.

The challenge for Trump is to maintain a balance between credibility and unpredictability. By generating uncertainty regarding the United States' response to aggression, his strategy could serve as a deterrent to formidable adversaries such as China or Russia. Nevertheless, it is possible that this strategy could backfire if these nations perceive his behavior as erratic and preemptively escalate conflicts.